But the article does not mention Israel's current programs to train soldiers from Ethiopia.

"Somalia: The World's forgotten catastrophe"

INDEPENDENT (U.K.)

9 February 2008

On the Web at:

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/africa/somalia-the-worlds-forgotten-catastrophe-778225.html

According to the UN, the worst catastrophe in Africa is not taking place in Kenya, or even Darfur. Fifteen years after the disastrous Black Hawk Down incident, Somalia has more refugees than any country in the world.

Saturday, 9 February 2008

Khalid Abdullahi lives down a winding dusty track, among cactus trees and chickens pecking at the rubbish piled up against rusting corrugated iron walls. In this anonymous corner of Mogadishu, a city destroyed a dozen times over in the past 17 years, he shares a dirt-floored shack with more than 20 brothers and sisters, aunts and uncles, a niece and nephews.

Khalid was nine the day his father died in 1993. "We were sitting here in this room when we heard a big noise," he says. The "big noise" was the sound of an American Black Hawk helicopter being shot down and crashing into Khalid's house.

Eighteen US Army Rangers were killed in the firefight that followed. Their broken bodies were dragged through Mogadishu's battle-scarred streets. An estimated 1,000 Somalis died that day too, although they didn't get a Hollywood film made about them.

The US had been leading a United Nations peacekeeping mission but following the Black Hawk Down incident US troops pulled out. The rest of the UN mission soon followed and Somalia was left to slide back into anarchy.

Propped up against the wall, hidden behind a mattress, is the nose cone of the Black Hawk. Khalid pulls it out and places the piece of black fibre-glass in the middle of the room. "The Americans said they were helping us," he says. I ask him whether he thinks they did. Khalid just smiles and doesn't answer.

There are no Black Hawk helicopters in Mogadishu today. No UN tanks patrolling the streets. But 15 years on, the United States is back in Somalia. CIA agents are operating in Mogadishu. Unmanned Predator drones circle above the city gathering intelligence. US forces have carried out at least four attacks inside the country in the past 12 months. Civilians in Somalia and neighbouring Kenya have been "extraordinarily rendered" to prisons in Ethiopia's capital, Addis Ababa, where they have been interrogated by US officials.

Last time the US arrived in Somalia in dramatic fashion: hundreds of marines swarmed on to the Mogadishu beach in the full glare of television news crews. This time there hasn't even been a press release. Officially, the US has no involvement in Somalia. It is a secret war, a third front in America's global war on terror. It is also a war that the US and its allies are losing.

On Christmas Day 2006, Ethiopia invaded its neighbour, Somalia. The aim: to drive out a coalition of Islamists ruling the capital, Mogadishu, and install a fragile interim government that had been confined to a small town in the west. But Ethiopia was not acting alone. The US had given its approval for the operation and provided key intelligence and technical support. CIA agents travelled with the Ethiopian troops, helping to direct operations.

The US believed al-Qa'ida was operating inside Somalia. The Union of Islamic Courts, which had ruled much of southern and central Somalia over the previous six months, was ruled by "East Africa al-Qa'ida cell individuals", said America's top Africa diplomat, Jendayi Frazer.

The US had a list of "high value" terror suspects who were allegedly being "sheltered" by the Courts. Fazul Abdullah Mohammed had been implicated in the 1998 US embassy bombings in Nairobi and Dar-es-Salaam, which killed 224 people. Abu Talha Al-Sudani and Saleh Ali Saleh Nabhan were believed to be behind the 2002 bombing in Mombasa that killed 13 people at an Israeli-owned hotel. A simultaneous attack on an Israeli aeroplane leaving Mombasa failed.

The Courts themselves were also a cause for concern, they said. Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys, one of the Courts' leaders, was on the US state department's list of suspected terrorists. Adan Hashi Ayro, the leader of al Shabaab, the military wing of the Islamic Courts, had trained in Afghanistan with Osama bin Laden and was al-Qa'ida's de facto leader in East Africa.

The Courts had promised a long battle. In the weeks leading up to the Ethiopian invasion hardliners within the organisation had called for a "jihad" against Ethiopia and threatened to invade Addis Ababa. In the end, their resistance lasted a matter of days. On 28 December, Sheikh Sharif Ahmed, the Courts' chairman, admitted defeat. The leadership scattered, most fleeing south towards a training camp called Ras Kamboni. Their fighters disappeared, melting back into Mogadishu.

The first US airstrike was carried out on 7 January 2007 – its first and only publicly acknowledged military operation inside Somalia since 1994. Two AC-130 helicopter gunships, flown from an airbase in eastern Ethiopia, carpet-bombed a convoy of trucks moving through Ras Kamboni, a fishing village near the Kenyan border that has also been home to an al-Qa'ida training camp.

A team of US special forces based in Kenya's Manda Bay flew in after the airstrike with orders to kill anyone left alive and find out who had died. The mission was instantly declared a success. Those attacked were "senior al-Qa'ida leadership", the Pentagon said. A Somali government official claimed Fazul had been killed; US officials later told the New York Times that Ayro had probably been killed. "There are many reasons to be hopeful," said Frazer. It wasn't quite "Mission Accomplished", but the inference was clear.

There was only one problem. According to local Somalis, and confirmed by western diplomats and aid officials in Nairobi, none of the dead was connected to the Courts. Instead, a group of pastoralists gathering around a fire to keep the mosquitoes away had been killed.

Fazul was still alive, as was Ayro, who returned to Mogadishu to lead the insurgency. Further air strikes took place – at least one in January and one in March. It would later be claimed that al-Sudani had been killed in one of those strikes. Again, non-American diplomats dispute that assertion. "They haven't got anybody," said one European official. "It has been an absolute disaster."

The public face of US operations in the Horn of Africa is situated in Djibouti, a tiny country perched on the edge of one of the most volatile regions in the world. Camp Lemonier, a former French Foreign Legion base beside Djibouti airport, is home to 1,600 US armed-forces personnel – the Combined Joint Task Force for the Horn of Africa.

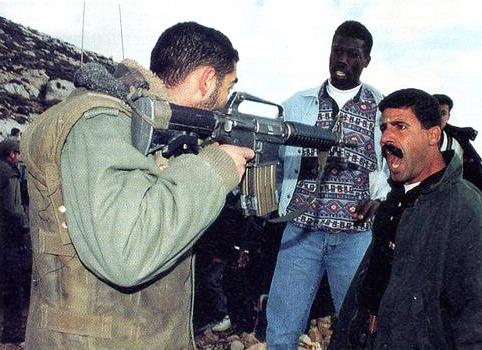

Their mission is "non-lethal", insists Lt Mike Czarnik. "We don't have people out there shooting things." Technically, he's right. The Task Force is engaged in "hearts and minds" operations: building schools, boreholes, and health clinics. But the task force also trains other militaries in the region, most notably the Ethiopians.

Captain Joe Cruz is the commander of Delta Company's 1st infantry. Most people at Camp Lemonier know him as the Scorpion King. Last year the task force's entire air-force capacity – four helicopters and two C130 gunships – was scrambled to Gode in eastern Ethiopia to evacuate Cruz after he was bitten by a scorpion. "It was a little embarrassing," he says.

Cruz had been leading the training of the Ethiopian military – just months before they invaded Somalia. "A lot of what we taught them was used to fight that global war on terror. We weren't training them to invade another country," he says. "But I know some of the guys went to Somalia."

Ethiopia and the US had already been working together on the Ethiopia-Somalia border, tracking suspected terrorists. "They are a very disciplined army, a very good fighting force," says Cruz. "They were trained by the Soviets. All their soldiers had trained in Russia."

The only problem was a lack of equipment. Each soldier had been issued an AK-47, but they were allocated just 10 rounds for training each year. Some of the weapons had been manufactured more than 40 years ago. Cruz gave the US embassy a list of weapons the Ethiopians could do with. "They got what they needed." He won't say what.

Somalia has been without a functioning central government since 1991. It is the archetypal failed state. Following the overthrow of Mohammed Siad Barre's military regime in 1991, the country was torn apart by feuding "warlords". Each had its own clan-based militia, armed to the teeth with AK47s, RPGs and driving around in "technicals" – jeeps with the top ripped off and an anti-aircraft missile welded to the back.

The lives of Somalia's 10 million people were gradually destroyed by endless civil wars, countless droughts and floods. Thirteen attempts at creating a new central government failed. A 14th established the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) in Nairobi in 2004.

While Somalia's newest politicians, many of whom doubled as Mogadishu warlords, swanned around in fancy Nairobi hotels, a new power base was growing in Somalia. During the 1990s Islamic Courts had been established in different parts of the city as a way of administering sharia justice in a city without law and order. By 2006 there were 11 such courts across Mogadishu. They each had their own militia but they had not, up to this point, begun working closely with one another.

It was the US which, inadvertently, brought them together. The Black Hawk Down incident in 1993 was a failed attempt to capture one of Mogadishu's biggest warlords, Mohammed Aideed. By 2006 the US no longer cared whether the warlords ran Somalia or not. What they cared about was al-Qa'ida.

The CIA's desperation to root out the men on their list saw them turn to some old enemies for help. CIA agents landed at tiny airstrips outside Mogadishu and handed briefcases full of crisp new $100 notes over to the same warlords who had chased the US out of Somalia in 1993. The warlords took the money and used it to take on the Courts. They formed themselves into the Alliance for the Restoration of Peace and Counter-Terrorism – before proceeding to do very little to find the supposed terrorists the CIA wanted caught.

The strategy backfired. The leaders of the courts united their militias and defeated the US-backed warlords. With the warlords finally gone, Mogadishu experienced something it hadn't had in a very long time – some semblance of peace and security.

"The streets in Mogadishu were full of women and kids," says Eric Laroche, the head of the UN's humanitarian operations in Somalia. "The kids were playing soccer."

It was not all sweetness and light. Public executions took place for alleged adultery, gunmen opened fire on people watching the football World Cup, and two foreigners were assassinated. But for many Somalis, the level of security the Courts brought trumped their over-zealous social policies.

But for the US the idea of an Islamic authority ruling Somalia was too much to bear. "They were scared of a Taliban-style state," said a diplomat in Nairobi. "But the country is 99 per cent Muslim. What's wrong with encouraging an Islamic democracy like Malaysia?"

A functioning central government of any stripe would be a start. By the time the warlords were defeated the TFG had managed to install itself inside Somalia. Mogadishu wasn't deemed safe enough, so the government found itself in the central town of Baidoa. Attempts by European diplomats to bring the TFG and the Islamic Courts together failed. The US and Ethiopia encouraged the TFG, led by a former warlord, Abdullahi Yusuf, not to negotiate.

In October 2006, four months after the warlords strategy had failed, Frazer travelled to Baidoa to meet President Yusuf. According to people present at the meeting, Frazer told Yusuf the US would help him "sweep out the Islamists". Ethiopia was also prepared to help. Since July 2006 Ethiopian troops had been in Somalia, training TFG forces.

Ethiopia, with its Christian government of a Christian and Muslim nation, had its own concerns. Prime Minister Meles Zenawi believed the Islamic Courts were providing support to rebel groups in eastern Ethiopia's Ogaden region. Meles was also alarmed by loose talk from Courts hardliners threatening to launch a "jihad" against Ethiopia.

Ethiopia has gone to war with Somalia twice before – in 1964 and 1977. Ethiopian troops also crossed the border in 1996 to attack a Somali Islamist group, al-Itihaad al-Islamiya, which was led by Sheikh Aweys.

In November 2006 General John Abizaid, then the commander of the US Central Command, visited Addis Ababa in November and met Zenawi. Abizaid was known to have concerns, warning Zenawi that Somalia could become "Ethiopia's Iraq". But the deal had already been done. US military officials were already discussing plans for the invasion with their Ethiopian counterparts.

The US provided key intelligence from spy satellites detailing the positions of the Courts' militias. Ethiopia would invade, drive out the Courts, install the TFG in Mogadishu, then help the US kill or arrest their key targets.

In Kenya, the US ambassador, Michael Rannenberger, urged Kenya to close its border with Somalia. US Navy ships sailed south from Djibouti and stationed themselves just off the southern coast. With the Ethiopians chasing the Courts leaders and terror suspects out of Mogadishu they would find themselves trapped in the swamps of southern Somalia.

The strategy failed. Within weeks of the invasion Al Shabaab had regrouped. Its leader, Ayro, was back in Mogadishu. Leaflets, headed "Heavy Warning", began circulating, threatening an insurgency against the Ethiopian troops. Young men with red scarves wrapped around their faces placed remote-controlled bombs by the side of the road, waiting for Ethiopian convoys to pass. "This is the start of the insurgency," one young man told me. "We will not give up."

And they haven't. Mogadishu has been rocked by almost daily violence. Hundreds of civilians have been killed in the crossfire, thousands injured. Ethiopia's original plan, drafted with the US, foresaw a two-month-long military operation. By the beginning of March last year Ethiopian troops would begin to withdraw. That hasn't happened. Instead, frustrated by the growing insurgency, Ethiopia has been forced to increase its numbers.

Ethiopia's "surge" began in October 2007. Ethiopia refuses to say how many troops it has inside Somalia but it was believed to be around 15,000. Since the surge, the numbers have almost doubled. An African Union force of 8,000 troops from Uganda, Burundi, Ghana and Nigeria was supposed to be taking over; as of December just a single battalion of 1,600 Ugandan troops has been deployed.

As the insurgency in Mogadishu has grown, so too has the influence of its hardline leaders. The conservatives who headed the Islamic Courts have been sidelined; even Aweys has seen his power slip. The Shabaab high command met in an undisclosed location somewhere in southern Somalia in early October 2007. They formed an organising committee of seven. It was the moment, one western diplomat said, when "the international jihadi wing took full control".

Aweys's ambitions had never stretched much further than reuniting Greater Somalia. (Following the 19th-century "scramble for Africa", France, Italy and Britain all claimed parts of Somalia. A fourth region was incorporated into northeastern Kenya, while the fifth became part of Ethiopia.)

Ayro's ambitions are far grander. Training camps have been re-established in southern Somalia. Dozens of villages and districts are handing over their administration to the Islamists. The group is well-trained and well-funded, with money from groups in Iran and Saudi Arabia. When Jendayi Frazer claimed the Islamic Courts were run by "East Africa's al-Qa'ida cell" she was wrong. But, said one Nairobi-based Somalia analyst, "It has become a self-fulfilling prophecy."

As America has lost its grip on southern and central Somalia it has turned its attention further north. Somaliland, formerly a British protectorate, declared itself independent in 1991, while Puntland, at Africa's most easterly tip, gained semi-autonomy from the rest of Somalia in 1998. Both provinces have their own intelligence services; both are funded by the US.

So far there appears to have been little reward. One Puntland Intelligence Service officer thinks he knows why. "The Americans know nothing," he said, sitting in a café in the port city of Bosasso. "They pay for information, but they don't know what's right and wrong." This officer insisted he gave only good information but knew of others who used their position to settle old scores.

Being part of the PIS is dangerous. A few days before he met me two of his colleagues had been murdered. The Islamic Courts, he said, have a lot of support in Puntland. Bosasso is also Somalia's most important port and much of the trade is controlled by businessmen with links to the Islamic Courts.

Puntland was the scene of another US attack in June 2007. A group of senior Courts leaders was believed to be hiding in the hills above a village called Bargal. Shots were fired from a US warship stationed off the coast. US officials denied the attack and claims by local Puntland leaders that several Courts officials had been killed could not be proved.

The June attack was a signal of the changing nature of US operations in Somalia. Following the attack contractors were hired with US money to rebuild Bosasso's crumbling runway. This was no aid project. Once completed, Bosasso, a steamy port city of 500,000 people, will be home to the third-largest airstrip in Africa. "The US wants to be able to land anything in Bosasso," said one senior diplomat based in the city. "Anything."

In a rare moment of candour earlier last year, the US special envoy to Somalia, John Yates, admitted to fellow diplomats that their strategy had failed. "We set the agenda and then we lost control," he said. One diplomat present at the meeting said the US was finally beginning to realise that the insurgents were winning.

Somalia is now experiencing its worst period of violence in two decades. The daily battles between Ethiopian-backed government forces and the insurgents have had a devastating impact on the population.

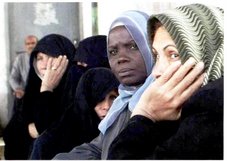

More than 600,000 people fled Mogadishu last year. Around 200,000 are now living in squalid impromptu refugee camps along a 15km-stretch of road outside the capital. According to UN officials it is the largest concentration of displaced people anywhere in the world. Those same officials now consider Somalia to be the worst humanitarian catastrophe in Africa, eclipsing even Darfur in its sheer horror.

Attempts at political reconciliation have been unsuccessful. The more moderate political leadership of the Courts has regrouped along with disillusioned MPs from the TFG and other opposition figures. But the Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia, as it is known, established itself in Eritrea, Ethiopia's sworn enemy. Eritrea has been accused by the UN of arming the Courts and the US has threatened to place Eritrea on its list of state sponsors of terrorism.

Divisions within the TFG have also hampered reconciliation efforts. President Yusuf and his prime minister, Ali Mohammed Gedi, never really got on. The final straw was a row over a donation of $32m Saudi Arabia made to the government for a national reconciliation conference. Gedi kept most of the money for himself. Frustrated by the impasse, the Americans took control. Gedi was summoned to Addis Ababa where he spent two days locked in meetings with US and Ethiopian officials.

In return for stepping down, Gedi was given asylum in the United States and was allowed to keep the remains of the Saudi money. He has bought a house in Los Angeles and US officials have negotiated a position for him at the University of California in Los Angeles.

No one will pay for Hawa Ali Abdi to move to Los Angeles. She lives under a tree. Along with her husband and their two children, two-year-old Hussein and three-month-old Fatuma, she fled Mogadishu in October after a wave of Ethiopian attacks aimed at rooting out insurgents.

Now she is in Afgoye, 40km down the road, part of the world's largest concentration of displaced people. There is no food and no water. Nowhere to go to the toilet and nowhere to get shelter for the night. Hussein is seriously malnourished and is now being treated at a local clinic run by Médecins Sans Frontières. The clinic was established by Dr Hawa Abdi, a Soviet-trained Somali doctor who has lived and worked here through every one of Somalia's past 17 years of hell.

"Of all the situations in Somalia," says Dr Abdi, "today is the worst. There is no food, no medicine, no education, no jobs, no hope. People are dying every day. It is a slow genocide. We are hopeless now. Hopeless."

________________________________