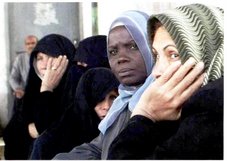

"Siege that spells slow death for the innocents:

"Sick patients requiring urgent medical care among those penned in hell-hole"

by Ed O’Loughlin In the Gaza Strip

SUNDAY HERALD (Scotland, U.K.)

Decewmber 9, 2007

On the Web at:

http://www.sundayherald.com/international/shinternational/display.var.1891492.0.0.php

FOR THREE weeks, seven-month-old Mohammed Abu Amra has been lying in Gaza's main paediatric hospital, suffering from immune deficiency and suspected cystic fibrosis.

His doctors do not have the drug they need to relieve his symptoms, which include fever and distressed breathing, racking his thin ribs at almost twice the healthy rate of breaths per minute.

Nor does any hospital in the sealed-off Gaza Strip have the equipment or expertise needed to clinically diagnose Mohammed's condition. For eight days his doctors have been waiting for a reply to their request to transfer the baby to a hospital in Israel. If it is not granted, they say, he will probably die.

"Because of the Israeli siege the number of patients who can travel is very limited," says paediatrician Dr Ahmed Shakat, standing over the child's bed in Gaza's al-Nasser hospital.

"In the past it took one day to transfer an urgent patient to Israel. Now I need maybe five, maybe 10, if it happens at all. The Israelis say it's because of security, but it means urgent cases can die. In the past we could have transferred him also to Egypt, but now that border is closed because of the siege."

Baby Amra is not expected to die quickly if denied proper treatment. Nor would any single factor or player be directly responsible for his death. If he dies it will be partly because he was sick, partly because he was weak, partly because he could not escape from Gaza, partly because the things he needed to survive were not provided to him quickly enough or in sufficient quantity; a variety of reasons that the Israeli government, the rival Palestinian factions and international humanitarian bodies all seek to blame on each other.

In this the child resembles the Gaza Strip itself, a real-life dystopia cut off from the outside world where, under the pressure of half a dozen or so slowly tightening screws, life is coming apart at every seam. Mahmoud Daher, Gaza director of the UN-affiliated World Health Organisation (WHO), says that the health service is where the effects of Palestinian infighting and Israel's blockade are showing most dramatically.

Last week WHO reported that out of the 782 Gaza patients to have sought specialist treatment outside the Strip since the siege was tightened in June, 100 have been granted permits by Israel to leave.

Of those, 27 were turned back to Gaza after being interrogated by Israeli security agents at the Erez crossing. Four died after their passage was delayed or refused; another seven died while waiting for permits in Gaza hospitals.

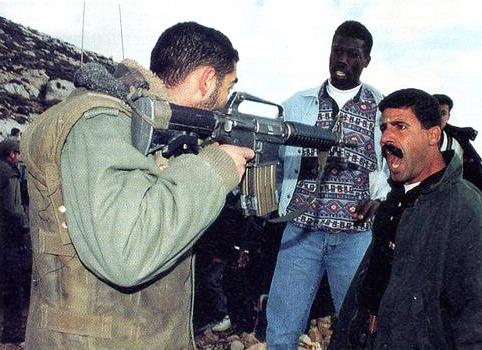

In October, an Israeli newspaper and two human rights groups charged that agents of the Israeli security organisation Shin Bet who are based at Erez were attempting to recruit patients or their parents as informers by threatening to prevent them gaining treatment.

Several who declined said they were turned back or subsequently refused passage for follow-up treatment on the grounds they were "security risks".

The Israeli government denied the allegation, claiming it was the Hamas government in Gaza which was somehow closing the crossings after it took control of the Strip from its Fatah rival in June. A spokesman also suggested that the rights groups did not have access to Shin Bet's secret information on the patients.

According to the WHO report, one-fifth of essential drugs and 31% of medical supplies were no longer available in Gaza by October and 11 out of 18 psychiatric drugs had run out in August, a time when health workers were observing a "growing proportion of the population experiencing psychological symptoms".

_____________________________________