"Overcoming speechlessness"by Alice Walker

July 18, 2009

On Ma'an News Agency, at:

http://www.maannews.net/eng/ViewDetails.aspx?ID=212871[Pulitzer Prize winning author and feminist Alice Walker writes about her visit to the Gaza Strip only weeks after the Israeli ceasefire in March. She travelled to the Strip with CODEPINK.]

And so I have been, once again, struggling to speak about an atrocity: This time in Gaza, this time against the Palestinian people. Like most people on the planet I have been aware of the Palestinian –Israeli conflict almost my whole life. I was four years old in 1948 when, after being subjected to unspeakable cruelty by the Germans, after a “holocaust” so many future disasters would resemble; thousands of European Jews were resettled in Palestine. They settled in a land that belonged to people already living there, which did not seem to bother the British who, as in India, had occupied the land and then, on leaving it, decided they could simply put in place a partitioning of the land that would work fine for the people, strangers, Palestinians and European Jews, now forced to live together. When we witness the misery and brutality still a daily reality for millions of people in Pakistan and India, we are looking at the failure, and heartlessness, of this plan…..

Houses, hospitals, factories, police stations, parliament buildings, ministries, apartment buildings, schools, went up in dust. The sight of one family in which five young daughters had been killed was seared into my consciousness.

The mother, wounded and unconscious, was alive. Who would tell her? I waited to hear some word of regret, of grief, of compassion, from our leaders in Washington, who had sent the money, the earnings of American taxpayers, to buy the bombs destroying her world. What little concern I became aware of from our “leaders” was faint, arrived late, was delivered without much feeling, and was soon overshadowed by an indifference to the value of Palestinian life that has corrupted our children’s sense of right and wrong for generations. Later our government would offer money, a promise to help “rebuild.” As if money and rebuilding is the issue. If someone killed my children and offered me money for the privilege of having done so I would view them as monsters, not humanitarians.

I consulted my companion, who did not hesitate. We must go, he said. The sooner we reach the people of Gaza, the sooner they’ll know not all Americans are uncaring, deaf and blind, or fooled by the media. He went on to quote Abraham Lincoln’s famous line about fooling the people. You can fool some of the people some of the time, but not all of the people all of the time. Americans, we know, are, for the most part, uninformed about the reality of this never-ending “conflict” that has puzzled us for decades and of which so many of us, if we are honest, are heartily sick. We began to pack.

…

Arriving in Cairo at three-thirty in the morning, my first task, assigned by the beautiful, indomitable and well loved co-founder of CODEPINK, Medea Benjamin, was to meet with her and the U.S. Ambassador to Egypt, Ambassador Scobey, at ten-thirty a.m. to ask for assistance in crossing the border into Gaza from Egypt. After a few hours rest, I appeared early for the meeting (concerned that Medea had not arrived yet) which, though cordial, would yield no help. Even so, I was able to have an interesting talk with the Ambassador about the use of non-violence. She, a white woman with a southern accent, mentioned the success of “our” Civil Rights Movement and why couldn’t the Palestinians be more like us.

It was a remarkable comment from a perspective of unimaginable safety and privilege; I was moved to tell her of the effort it took, even for someone so inherently non-violent as me, to contain myself during seven years in Mississippi when it often appeared there were only a handful of white Mississippians who could talk to a person of color without delivering injury or insult. That if we had not been able to change our situation through non-violent suffering, we would most certainly, like the ANC, like the PLO, like Hamas, turned to violence. I told her how dishonest it seems to me that people claim not to understand the desperate, last ditch, resistance involved in suicide bombings; blaming the oppressed for using their bodies where the Israeli army uses armored tanks. I remembered aloud, us being Southerners, my own anger at the humiliations, bombings, assassinations that made weeping an endless activity for black people, for centuries, and how when we finally got to a court room which was supposed to offer justice, the judge was likely to blame us for the crime done against us and to call us chimpanzees for making a fuss. Medea arrived at this point, having been kept circling the building in a taxi that never landed, and pressed our case for entry into Gaza. While appearing sympathetic to our petition, our ambassador emphasized it was dangerous for us to go into Gaza and that her office would be powerless to help us if we arrived there and were injured or stranded. We were handed some papers telling us all the reasons we should not go.

… She handed me an illustrated postcard that showed plainly what the situation between Israel and Palestine came down to: in 1946 the Palestinians owned Palestine, with a few scattered Jewish villages (picture one); some years later, under a United Nations plan for partitioning, Palestine and Israel would each own roughly half of the land (picture two); from 1949-1967 the Israel “half” grew by about a third; after the 1967 war, Israel doubled its land mass by virtue of the land it took from Palestine at that time. The last picture shows the situation in 2008: Palestinian refugees (in their own country) live in camps in the West Bank and Gaza, and the whole land is now called Israel. On the back of this card are words from former Israeli president Ariel Sharon, known as the butcher of Sabra and Shatila (refugee camps in Lebanon where he led a massacre of the people) where he talks about making a pastrami sandwich of the Palestinian people, riddling their lands with Jewish settlements until no one will be able to imagine a whole Palestine. Or know Palestine ever existed.

No one can imagine a whole Turtle Island, either; now known as the United States of America, but formerly the land of Indigenous peoples. The land of some of my Native ancestors, the Cherokee, whose homes and villages were obliterated from the landscape where they’d existed for millenia, and the Cherokee forced – those who remained – to resettle, walking “the trail of tears,” a thousand miles away. This is familiar territory. As is the treatment of the Palestinian people…

It was moving to hear the stories of why the Jews on our Gaza bound bus were going to Palestine. Many of them simply said they couldn’t bear the injustice, or the hypocrisy. Having spoken out against racism, terrorism, apartheid elsewhere, how could they be silent about Palestine and Israel? Someone said her friends claimed everyone who spoke out against Israeli treatment of Palestinians was a. a self-hating Jew (if Jewish) or anti-Semitic (though Palestinians are Semites, too). She said it never seemed to dawn on the persons making the anti-Semitic charge that it is Israel’s behavior people are objecting to and not it’s religion. As for being self-hating? Well, she said, I actually love myself too much as a Jew to pretend to be ignorant about something so obvious. Ignorance is not held in high regard in Jewish culture.

… I came out of this reverie to hear the story of Cindy and Craig Corrie, the parents of Rachel Corrie. Rachel Corrie was murdered when she tried to stop an Israeli tank from demolishing a Palestinian house. I was struck by her parents’ beauty and dignity. Cindy’s face radiates resolve and kindness. Craig’s is a study in acceptance, humility, incredible strength, and perseverance. Rachel had been working in Palestine and witnessed the ruthlessness of the deliberate destruction of Palestinian homes by the Israeli army, most surrounded by gardens or small orchards of orange and olive trees, which the army consistently uprooted.

No doubt believing the sight of a young Jewish woman in a brightly colored jumpsuit would stop the soldier in the tank she placed herself between the home of her Palestinian friends and the tank. It rolled over her, crushing her body and breaking her back. The Corries spoke of their continued friendship with the family who had lived in that house. Everywhere we went, after arriving in Gaza, locals greeted the Corries with compassion and tenderness. This was particularly moving to me because of a connection I was able to make with another such sacrifice decades ago in Mississippi, in 1967, and how black people became aware that there were some white people who actually cared about what was happening to them.

…Rolling into Gaza I had a feeling of homecoming. There is a flavor to the ghetto. To the Bantustan. To the “rez”. To the “colored section.” In some ways it is surprisingly comforting. Because consciousness is comforting. Everyone you see has an awareness of struggle, of resistance, just as you do. The man driving the donkey cart. The woman selling vegetables. The young person arranging rugs on the sidewalk or flowers in a vase. When I lived in segregated Eatonton, Georgia I used to breathe normally only in my own neighborhood, only in the black section of town. Everywhere else was too dangerous. A friend was beaten and thrown in prison for helping a white girl, in broad daylight, fix her bicycle chain. But even this sliver of a neighborhood, so rightly named the Gaza strip, was not safe.I thought of how, in the U.S. the first and perhaps only bombing on U.S. soil, prior to 9/11, was the bombing of a black community in Oklahoma. The black people who created it were considered, by white racists, too prosperous and therefore “uppity.” Everything they created was destroyed. This was followed by the charge already rampant in white American culture, that black people never tried to “better” themselves. There is amble evidence in Gaza that the Palestinians never stop trying to “better” themselves. What started as a refugee camp with tents, has evolved into a city with buildings rivaling those in almost any other city in the “developing” world. There are houses, apartment buildings, schools, mosques, churches, libraries, hospitals.

Driving along the streets, we could see right away that many of these were in ruins. I realized I had never understood the true meaning of “rubble.” Such and such was “reduced to rubble” is a phrase we hear. It is different seeing what demolished buildings actually look like. Buildings in which people were living….

Only the woman with one child has trouble speaking. When I turn to her, I notice she is the only woman wearing black, and that her eyes are tearing. Unable to speak, she hands me instead a photograph that she has been holding in her lap. She is a brown-skinned woman, of African descent, as some Palestinians (to my surprise) are; the photograph is of her daughter, who looks European. The child looks about six years old. A student of ballet, she is dressed in a white tutu and is dancing. Her mother tries to speak, but still cannot, as I sit, holding her arm. It is another woman who explains: during the bombardment, the child was hit in the arm and the leg and the chest and bled to death in her mother’s arms. The mother and I embrace, and throughout our meeting I hold the photograph of the child, while the mother draws her chair closer to mine.

What do we talk about?

We talk about hatred.

… Following their example of speaking of their families, I talk about my Southern parents’ teachings during our experience of America’s apartheid years. When white people owned and controlled all the resources and the land, in addition to the political, legal and military apparatus, and used their power to intimidate black people in the most barbaric and merciless ways.

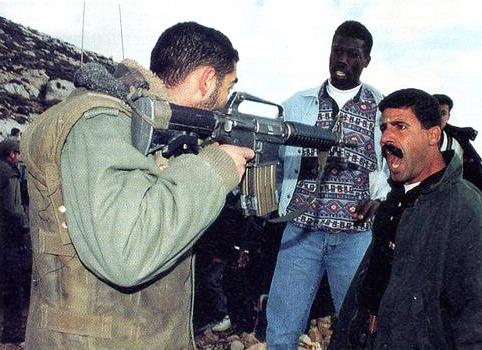

These whites who tormented us daily were like Israelis who have cut down millions of trees planted by Arab Palestinians; stolen Palestinian water, even topsoil. They have bulldozed innumerable villages, houses, mosques, and in their place built settlements for strangers who have no connection whatsoever with Palestine; settlers who have been the most rabid anti-Palestinian of all, attacking the children, the women, everyone, old and young alike, viciously, and forcing Palestinians to use separate roads from themselves.It feels very familiar, I tell them, what is happening here. When something similar was happening to us, in Mississippi, Georgia, Alabama, I say, our parents taught us to think of the racists as we thought of any other disaster. To deal with that disaster as best we could, but not to attach to it by allowing ourselves to hate. This was a tall order, and as I’m talking, I begin to understand, as if for the first time, why some of our parents’ prayers were so long and fervent as they stayed there, long minutes, on their knees in church. And why people often wept, and fainted, and why there was so much tenderness as people deliberately silenced themselves, or camouflaged atrocities done to or witnessed by them, using representative figures from the Bible.

… She laughs, this handsome woman; then speaks earnestly. We don’t hate Israelis, Alice, she says, quietly, what we hate is being bombed, watching our little ones live in fear, burying them, being starved to death, and being driven from our land. We hate this eternal crying out to the world to open its eyes and ears to the truth of what is happening, and being ignored. Israelis, no. If they stopped humiliating and torturing us, if they stopped taking everything we have, including our lives, we would hardly think about them at all. Why would we?

There is, finally, a sense of overwhelm, trying to bring comfort to someone whose sleeping child has been killed and buried, a few weeks ago, up to her neck in rubble; or a mother who has lost fifteen members of her family, all her children, grandchildren, brothers and sisters, her husband. What does one say to people whose families came out of their shelled houses waving white flags of surrender only to be shot down anyway? To mothers whose children were, at this moment, playing in the white phosphorous laden rubble that, after 22 days of bombing, is everywhere in Gaza? White phosphorus, once on the skin, never stops burning.

There is really nothing to say. Nothing to say to those who, back home in America, don’t want to hear the news. Nothing to do, finally, but dance.

… The ecstasy, sublime. I was conscious of exchanging and receiving Spirit in the dance. I also knew that this Spirit, which I have encountered in Mississippi, Georgia, the Congo, Cuba, Rwanda and Burma, among other places, this Spirit that knows how to dance in the face of disaster, will never be crushed. It is as timeless as the wind. We think it is only inside our bodies, but we also inhabit it. Even when we are unaware of its presence internally, it wears us like a cloak.

I could have gone home then. I had learned what I came to know: that humans are an amazing lot. That to willfully harm any one of us is to damage us all. That hatred of ourselves is the root cause of any harm done to others, others so like us! And that we are lucky to live at a time when all lies will be exposed, along with the relief of not having to serve them any longer. But I did not go home. I went instead to visit the homeless…

The full text of Alice Walker’s writing on her CODEPINK trip can be found at:

http://www.alicewalkersblog.com/2009/07/overcoming-speechlessness-poet.html_________________________________________