----------------------------------

Israel has murdered tens of thousands in Lebanon.

One famous example was at the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps.It only took the Israeli military, and their Phalangist allies, two days to massacre over 3,000 people in those camps, after first making sure to either kill or exile all resistance fighters from Beirut:

"Between 3,000-3,500 men, women and children were massacred within 48 hours between September 16 and 18, 1982", writes journalist Amnon Kapeliouk, one of the first reporters who arrived on the scene.

Kapeliouk's book is on the Web, as a single Microsoft Word document, at:

http://www.geocities.com/indictsharon/Kapeliouk.doc

"SABRA & CHATILA: INQUIRY INTO A MASSACRE"

by Amnon Kapeliouk

Translated and edited by Khalil Jehshan

FOREWORD by Abdeen Jabara

The unprecedented crimes against humanity committed by Nazi leaders before and during World War II raised the question as to how world society might impose punishment for acts that were so heinous as to shock the collective conscience of the world.

Contemporary international law of war developed by the War Crimes Tribunals at Nuremberg at the end of the Second World War established at least three categories of crimes against the world community, and, therefore, punishable offenses.

These crimes are: crimes against the peace, war crimes and crimes against humanity.

War crimes and crimes against humanity have included mass murder of civilians (now termed genocide), and are regarded as crimes both in times of peace and war.

The specific language contained in the Charter of the International Military Tribunal that sat at Nuremberg provides that crimes against humanity consist of "murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population, before or during the war, or persecutions on political, racial, or religious grounds in execution of or in connection with any crime within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal, whether or not in violation of the domestic law of the country where perpetrated.

The International Tribunal was established through the London Agreement of the four principal Allied powers and adhered to by twenty-three states. The establishment of the Tribunal in Europe and the Far East was a major development in establishing basic international criminal law precepts and the right of the international community to exact penalties for their violation.

The Nuremberg Principles, as they have come to be called, have established that:

A. War crimes and crimes against humanity are committed against the world community and not just the victims of the crime(s) and therefore the world community has the right to prosecute and punish, regardless of the identity of the victims.

B. International law provides the authority to try those charged with such crimes in municipal courts.

C. Acts which are lawful or even required by domestic law are nevertheless criminal if they violate the law of war; that is, the claim of superior orders is no defense.

These Nuremberg Principles have been reflected in the adoption of the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 for the Protection of War Victims. These acts are termed "grave breaches" of the Convention. The Conventions further provide that the national states which are parties to the Convention shall enact legislation to provide effective penal sanctions for persons who commit the "grave breaches."

Each state is also obliged to search for such persons, apprehend them, and to either bring them to trial or turn them over to the other Party to the Convention for prosecution.

The provisions of the four Conventions have been expanded in a Protocol of July 1977, to extend to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts.Geneva Convention No.IV of August 12, 1949, Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, provides generally that "protected persons" are to be treated humanely under all circumstances without any distinctions based on race, religion, sex, or political opinion. It states that the signatory states:"... specifically agree that each of them is prohibited from taking any measure of such a character as to cause the physical suffering of protected persons in their hands.

This prohibition applies not only to murder, torture, corporal punishment, mutilation, and medical or scientific experiments not necessitated by the medical treatment of a protected person, but also to any other measure of brutality whether applied by civilian or military agents.

"These crimes against humanity have been incorporated in a more enduring form in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide adopted by the United Nations on December 9, 1948, and ratified by a number of states, including Israel.

This Convention provides that genocide is a crime under international law.

Genocide is defined in the Convention as including any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group, such as:

A. killing members of the group

B. causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group.

Genocide, conspiracy to commit genocide, direct and public incitement to commit genocide, attempt to commit genocide or complicity in genocide are, under the Convention, punishable.

Thus, the Convention incorporates the traditional requisites in criminal law that there must be both an act, or an omission to act where a legal duty exists, and the intent by the actor or non-actor that the result occur. Enforcement of the Convention involves the incorporation of genocide into domestic law by the signatory states and the trial of violators by competent domestic tribunals, since there does not exist an international criminal court with jurisdiction over such crimes and recognized by the signatory states.

The attention given to "crimes against humanity" by the Nuremberg principles, ''grave breaches'' by the Geneva Conventions and genocide by the Genocide Convention reflects the demand of the world community that the behavior of peoples and governments be made to conform to fundamental standards of human rights as a matter of state policy.

It is against this demand that the massacres of Lebanese and Palestinian civilians in Sabra and Shatilla camps in September 1982, must be examined.* * *

The evidence presented here by Amnon Kapeliouk, the testimony given at the Kahan Commission, and the independent news reports about the massacres raise serious questions regarding the legal culpability of the principal Israel and Lebanese actors in the slaughter in Sabra and Shatilla camps.

These questions of Criminal, as opposed to political culpability, remain to be dealt with. The Palestinian people are the most aggrieved party, but have no ability to initiate criminal prosecution proceedings. They have no state which can become a party to the several Conventions relating to crimes against humanity.

International law placed Israel under a direct, unequivocal duty to protect the civilian population in the refugee camps.

Israel not only failed to carry out this responsibility, but actively facilitated the arming and provisioning of the armed militia groups which entered the camp.

Israel prevented the flight of the civilian population from the camps.

Furthermore, it was the Israeli occupation of West Beirut which secured the approaches to the Sabra and Shatilla camps. Even if there was no coordinated plan between Israeli military officers and Lebanese Forces leadership, Israel remains culpable for its failure to provide even a modicum of protection to the civilian population.

These factors, together with the numerous anti-Palestinian statements such as Prime Minister Begin's remark in the Knesset that Palestinians were "two-legged beasts,'' must be seen as direct and public incitement to commit genocide, complicity in genocide or conspiracy to commit genocide.

The Genocide Convention demands proof of intent. This is sufficiently established by several facts. Reports to Israeli generals that a massacre was transpiring were not checked. They were not transmitted to superiors, nor were any steps taken to stop the killing until a considerable period of time had elapsed.

The most telling piece of evidence is that none of the perpetrators have been apprehended either for trial by Israeli courts or to be handed over to Lebanese authorities.

Israeli military and intelligence officials obviously knew the identities of the armed men who entered the camps between September 16 and 18.

Indeed, one of the Phalangists who participated in the massacres traveled to Israel for an interview on Israeli television.

Israeli cameramen in West Beirut filmed the Phalangists. Some of their pictures were published and others shown on Israeli television.

Many of these militiamen continued to operate in that portion of Lebanon occupied by Israeli soldiers.As a signatory to both the Geneva Conventions and the Genocide Convention, Israel was legally bound to arrest and try those persons who were both directly and indirectly involved in the wanton slaughter in Sabra and Shatilla.

In addition to these international provisions, Israeli domestic precedent established in the trial of Adolph Eichmann provided a legal framework in which these provisions could have been carried out. Israel has not done so, and one might ask why if the Begin government were not directly involved ... The Kahan Commission was the result of domestic and international protest. Despite the positive aspect of its work, the Commission had limited powers. It was further constrained by the political considerations involved in Israel's invasion of Lebanon, Israel's unrelenting negation of Palestinian national rights, and the unwillingness to recognize that horrible crimes against civilians were committed by Israel during the invasion of Lebanon in the name of Israeli security.

If a court does not sit in judgment of those who committed those crimes, perhaps history will.

FOREWORD by the Author

The inquiry presented in this book is the product of a task initiated the day after the massacre of Sabra and Shatila. It is based on testimony by dozens of Israelis (both civilian and military), Palestinians, Lebanese, and foreign journalists. We have relied heavily on the Israeli, Lebanese, and international press; the depositions made before the Israeli judiciary commission of inquiry; the official proceedings of the Knesset (Israeli Parliament); the monitoring services of Middle East radio stations; the dispatches of international press agencies; and documents of Israeli, Palestinian and Lebanese origin.

We have scrutinized the collected information, voluntarily discarding all data that could not be confirmed beyond the shadow of a doubt. -- A.K.

November, 1982

--------------------------------------

I

Tuesday, September 14, 1982

OPERATION "IRON BRAIN"

At 4:00 P.M., a massive bomb blast rocked East Beirut. A charge of 50 kg of TNT, equipped with a Japanese remote-controlled explosive device, totally demolished the headquarters of the Kata'ib Party (the Christian Phalange).

The charge was placed on the second floor of the building which is located in the Ashrafiyeh neighborhood. Bashir Gemayel, the new president of Lebanon, elected three weeks earlier (August 23, 1982), was chairing a meeting of senior Phalange Party officials in Beirut.

The meeting, regularly held every Tuesday, was meant this time as a farewell to his comrades, eight days prior to his inauguration.The three-story yellow building on Sasseen Street was situated on a hill overlooking the Museum Crossing which has separated the two sectors of the Lebanese capital since the beginning of the civil war. Other apartments in the surrounding area were also heavily damaged. Immediately, rescue teams rushed to the scene.

The Israeli Army also dispatched two helicopters carrying medics and specialized teams to clear the debris. Quickly, the Israelis arrived on the site in large numbers. Several armored troop carriers (M-113s), which pushed their way through the narrow streets of the neighborhood tearing up parked cars on both sides, took position around the area of the explosion. They were soon joined by half-tracks and many jeeps.

Helmeted Israeli soldiers, equipped with bulletproof vests, filled the streets of Ashrafiyeh.The first news reports concerning the fate of the young president were contradictory. The Phalanges radio announced that Bashir, 34 years of age, was not unharmed but "personally directed the rescue operations." This information immediately evoked cries of relief throughout the neighborhood, accompanied by traditional volleys of bullets fired in the air as a sign of joy. Another ratio station reported that ''Bashir is only slightly wounded in the leg and has come out of the rubble." At 7:30 P.M., the voice of Lebanon, the official broadcasting organ of the Phalangist Party, announced that the fate of Bashir Gemayel was still uncertain.

However, when the radio station replaced its usual programming with classical music, as did the Lebanese state radio, there was no doubt that "Sheikh Bashir" was dead.As in the case of the attack that took the life of the Egyptian president, Anwar Sadat, on October 6, 1981, American television networks were the first to broadcast the news. Bashir Gemayel, president-elect of Lebanon, was assassinated.

At 10:30 P.M., the Lebanese Forces (the "unified Christian militias," of which the Phalangists are the backbone) confirmed through a telephoned communiqué that the body of Bashir Gemayel had been retrieved from the ruins of the building. It was an Israeli officer who identified the mutilated corpse. The rescue teams found twenty-four other bodies, including those of three high-ranking officials of the Kata'ib Party led by Pierre Gemayel, father of the slain president-elect. Sixty other people were injured.Lebanon was in a state of shock. Speculation began as everyone tried to guess the identity of those behind the assassination attempt.

Phalangist officials whispered that "there were accomplices on the inside.'' One party official affirmed to an Israeli journalist that, ''Many stand to benefit from the assassination of the president-elect, from the PLO and the Syrians to the other extreme...."

The assassination of Bashir Gemayel was a painful blow to Israel. The slain president was the sworn enemy of the Palestinians. He did not hesitate to declare in an interview published in Le Nouvel Observateur (June 19-25, 1982) that, in the Middle East, "there is one people too many: the Palestinian people." His adversaries called him, "the president supported by Israeli bayonets."

Gemayel, in fact, collaborated with Israel throughout the civil war in Lebanon. This collaboration became manifest at the outset of the Israeli-Palestinian war on June 4, 1982.

Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Defense Minister Sharon considered him the man who would sign a peace treaty with them, based on his previous promises. Begin made this public on July 17, 1982. Addressing a massive Likud demonstration held in Tel Aviv, the prime minister announced before the 250,000 people in attendance: "Before the end of this year, we shall have a peace treaty with Lebanon."

Indeed, the election of Bashir Gemayel as president of Lebanon was the first clear political victory for General Sharon in this war. Until then, adversaries continued to remind him of his failure to achieve his declared objective in Lebanon, that is, the destruction of the PLO (Palestine Liberation Organization) and its leadership. Some added that, to the contrary, this organization had emerged politically stronger on the international scene by virtue of the ordeal it had undergone. Several weeks of deadly war, during which the destruction and civilian losses were considerable (18,000 dead and 30,000 injured according to Lebanese statistics), have resulted in decreasing public support for Israel around the world, including the United States.

Even the Jewish communities were torn apart, particularly over the massive bombardment of West Beirut. Detractors of the Begin policies ascertained that the announcement of the "Reagan Plan" on September 1 had put an end’s to Begin's dreams of annexing the West Bank and Gaza. Furthermore, the state of Israel was itself deeply divided perhaps as never before with many Israelis perceiving this war as an ill-matched battle between a Palestinian David and an Israeli Goliath.

This time Israel was no longer with its back to the wall. Instead, this was actually the status of its adversary, the Palestinians. In short, the invasion of Lebanon was an unpopular war, with large numbers of opponents who did not wait for its end to begin demonstrating against it -an unprecedented phenomenon in the history of the Jewish state.

Up to that time, Defense Minister Ariel Sharon, the true architect of the Israeli offensive, had responded to these criticisms with one word: patience. "Patience, gentlemen," he repeated often, "and we shall witness the fruits of this war." By mid-August, the time was ripe for him to lay down his trump card; Bashir Gemayel, his candidate, was elected president of Lebanon on August 23, 1982.

Thus within the framework of his overall strategy for the Middle East, the new order which General Sharon aspired to impose on Lebanon began to take shape. Bashir Gemayel, whose chances of assuming the presidency of Lebanon were nil in the absence of Israeli tanks, was elected despite everyone. Thus, Ariel Sharon was able to legitimately celebrate his victory, and he did not deny himself the pleasure of doing so.

The prime minister of Israel was the first to send a telegram of enthusiastic congratulations to the new president immediately after his election. The message read:

"All my congratulations from the bottom of my heart on your election. May God protect you, dear friend, in carrying out your important historic task for the freedom of Lebanon and its independence. Your friend, Menachem Begin."

The election of Gemayel crowned Israeli activity in Lebanon, an activity carried out covertly but ceaselessly since 1976 to make the Phalangists and their young military leader, Bashir Gemayel, the rulers of the country. The Israelis used everything to achieve this goal; military assistance, training Phalangist troops in special camps inside Israel, coordination of operations and intelligence services, and finally meetings between Phalangist commanders and Israeli leaders.

At first, this meant Labor party leaders. However, since May 1977, it has involved members of the Likud government. This collaboration between the two parties grew constantly.

Therefore it was not accidental that the Israeli chief of staff, General Raphael Eitan, declared after the assassination of Bashir Gemayel that: "He was one of our own.” Despite this history of collaboration, the first signs of uneasiness began to surface in Israel the day after "Sheikh Bashir" was elected. The new president did not seem very enthusiastic about what interested Begin and Sharon in the highest degree, namely, the prompt signing of a peace treaty. Initial Israeli pressure to hasten progress on this decision was exerted very quickly, but Bashir Gemayel explained that such a treaty would alienate Lebanon from the Arab world whose assistance was necessary for the reconstruction of his devastated country. To the Israelis, who persistently demanded that he begin to honor his debts, Bashir Gemayel responded that the time had not yet arrived, and that he must achieve national consensus and reconciliation before he could sign a peace treaty.

On the night of September 1, fifteen days prior to his assassination, Bashir Gemayel met secretly in Nahariyya, a coastal town in northern Israel, with his three principal interlocutors: Prime Minister Begin, General Sharon, and Foreign Minister Yitzhak Shamir. The conflict then entered its acute phase. Begin, who had initiated the meeting, thought that the new president was reneging on his commitments. He demanded the signing of a peace treaty which, in his view, would assume a major importance in the Middle East.

Bashir answered: "Signing a peace treaty with Israel today is like placing an explosive charge in the heart of the Middle East." He urged Begin to show patience by waiting until he (Gemayel) succeeded in stabilizing his power. "A de facto peace, agreed, but a peace duly signed, not until later," Gemayel said, without specifying any time framework. Ariel Sharon, who displayed his impatience throughout the encounter, peremptorily told Bashir Gemayel: "I am a man who likes to settle matters quickly. I am afraid that you might slip through our fingers." At this stage, tension reached its highest point.

According to sources close to Gemayel, the latter put his wrists up saying: "If you want to arrest me, all you have to do is handcuff me. Remember that you are talking to the president of Lebanon, and not to an Israeli vassal. We have our reasons." The discussion, which began at 11:00 P.M., continued in this manner until 3:00 A.M. The first news of the meeting was leaked less than twenty-four hours later.

The official Israeli radio itself confirmed the meeting. Bashir Gemayel fumed with anger. He was certain that the publicity surrounding this encounter was meant to compromise him. No one took his instant denial seriously. From that moment on, he refused to meet with the Israelis, except for once, on September 12, two days before his assassination, when he joined General Sharon at Bikfaya, Gemayel's hometown. Gemayel expressed his anger at the news leaks regarding their preceding meeting. He then reiterated his demand for a time extension sufficient to stabilize his situation in Lebanon, and to rebuild his relations with the Arab world, which accepted his election with caution.

In a meeting with Muslim leader Sa'eb Salam, Bashir openly complained of the pressures brought to bear upon him by the Israelis to conclude a peace treaty. In addition, Bashir directly contacted the editor-in-chief of a large Lebanese daily, L'Orient-le-Jour, admitting to him that he had gone to Nahariyya to meet with Begin.

He asked the newspaper to help him convince Israel that a peace treaty at this precise time was tantamount to partitioning the country. As a result, the ice was broken between the new president and the Muslims. At the same time, his relations with Israel continued to deteriorate.

However, Sharon was not prepared to give up. A week after the secret encounter in Nahariyya, he announced at a public meeting in Kiryat Shmonah, that if Lebanon failed to sign a peace treaty with Israel, he would establish a "security belt" extending 40 to 50 kilometers into southern Lebanon.

The area, said Sharon, would be given a legal status different from the rest of Lebanon. Quite often, sources close to General Sharon would state that without a peace treaty,

"We shall remain in south Lebanon. And since Syria will stay in the Bekaa Valley, then Gemayel will find himself president of the Beirut area."

The independent Israeli daily, Ha'aretz, reacted furiously. In an editorial published two days after the Sharon statement, the newspaper reproached him about "his edicts and threats," comparing him with "a Roman proconsul trying to dictate foreign policy to Lebanon."These remarks did not seem to impress the defense minister.

On the contrary, to clearly demonstrate his resolve, he expanded the zone in south Lebanon controlled by Major Sa’ad Haddad, a dissident Lebanese officer, unconditionally allied with and totally dependent on Israel.

Sharon also ordered the Israeli Army to prevent Phalangist forces from entering south Lebanon. During the early days of September, Israeli forces went so far as to forbid the Phalangists from holding a meeting in Sidon because they refused to display signs calling for a peace treaty between Lebanon and Israel.

On September 13, Bashir Gemayel granted Time Magazine an interview, his last, which was published on September 20. In it, he affirmed anew that peace with Israel would "come in due time." He identified his top priority objective as the restoration of the Lebanese government's authority, and its responsibility "for security on all Lebanese soil."

In Israel, this declaration was understood as the willingness to exclude Sa'ad Haddad from the enclaves he occupied in south Lebanon, and perhaps to bring him before a military tribunal for desertion. Still, Menachem Begin had warned Gemayel at their Nahariyya meeting not to take any improper action against his protégé, declaring in a threatening tone: "We defend our friends•" Thus, in view of the attitude which the president-elect of Lebanon seemed to adopt, the mood among Israeli leaders became rather morose.

Some were beginning to say plainly:

We have brought Gemayel to power with our might, and now he wants to build a career at our expense. Indeed, up to this time, there were two obvious tendencies among Israeli leaders: the first, traditionally mistrustful of Bashir accused him of knowing only how to receive but never giving anything in return.

The second, to the contrary, claimed that he was unable to "deliver" until he achieved his aim, i.e., assuming power, with Israeli assistance. Indisputably, this last tendency had begun to weaken by the hour.The debate was abruptly ended by the explosion that rocked Ashrafiyeh, creating a completely new situation. The news of the attack against Gemayel reached General Sharon shortly after it was executed.

Sharon immediately decided to benefit from the situation by entering West Beirut. He had wanted to conquer the western part of the Lebanese capital since the beginning of the war. According to the plan originally forecast, the Phalangist forces were to enter West Beirut at the end of the first week of the war, upon the arrival of Israeli forces at the outskirts of the city.

Yet, the "Phalangist allies" never fulfilled their part of the agreement, owing to weakness or for political reasons. Meanwhile, the Palestinian and progressive Lebanese forces were organized and well braced inside West Beirut, thus creating a risk of high casualties on the Israeli side in case of an assault. Nevertheless, this did not dissuade General Sharon.

Important Israeli officers who participated in the siege of Beirut -including Eli Geva, who resigned at the end of July to protest the inevitable attack on West Beirut- have since revealed that preparations for the assault were well under way during the long siege. The only thing lacking was the order to execute the plan. Each unit was assigned the task of laying siege to a neighborhood or a particular bloc of the city, and was specifically trained for that purpose.

According to those same officers, Sharon was pressuring the politicians to give him a green light to proceed with the operation.During this time, the international community intervened and reached a solution for the withdrawal of PLO forces and Palestinian leaders from Beirut, under the protection of a multinational force made up of American, French, and Italian troops. On August 21, the first French elements disembarked at the port of Beirut.

Thereafter, the entry of Israeli forces into West Beirut became impossible, at least as long as units of the international force remained in town. Israel then interceded with the United States for the latter to abide by its promise to withdraw the Marines as soon as possible after the PLO departure from Beirut on September 1. On the other hand, Lebanese leaders undertook futile efforts to convince the French authorities to maintain their troops in the city and help the Lebanese Army assume control of West Beirut.

On September 13, the eve of Bashir Gemayel's assassination and the Israeli entry into West Beirut, the last 850 French paratroopers and infantrymen of the Multinational Force left town, ten days prior to the expiration of their mandate.

The Israeli Deputy Chief of Staff, Major General Moshe Levi, stated in a radio interview broadcast on the Jewish New Year, two days after the entry of Israeli troops into West Beirut: "It was totally clear to us that sooner or later we would have to verify for ourselves, on the scene, whether all the terrorists had really left West Beirut."

Ze'ev Schiff, the authoritative military correspondent of Ha'aretz, revealed that, even prior to the assassination of Bashir Gemayel, the Israeli Army anticipated reaching the PLO headquarters to capture Palestinian leaders who might be found there, and, more important, to seize the documents left on the premises.

However, the Palestinians had anticipated this eventuality and took the necessary precaution of putting their most important documents on microfilm, which they carried out with them.In an interview granted to Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci two weeks before the Israeli Army entered West Beirut, Sharon denied having even envisioned an assault. However, he added: "Had I been convinced that we had to enter Beirut, nobody in the world would have stopped me. Democracy or not, I would have entered even if my government didn't like [it]."

In Israel, his declaration came as a bombshell, to the point that he had to deny making these statements and insist that he was misquoted. However, Sharon did in fact make these statements on September 14.

After the attack against the Lebanese president-elect was announced, Sharon undertook preparations to enter the western section of the city. He dispatched his chief of staff to East Beirut. An officer in the Lebanese Internal Security, who was present in the area of the Beirut International Airport, has since revealed to the French News Agency that an Israeli airlift began on September 14 at 6:00 P.M.

Tanks and soldiers were unloaded from that time on. When the official announcement of the death of Bashir Gemayel was made, Sharon contacted Prime Minister Begin. Together, the two men decided to enter West Beirut without prior consultation with the government. Foreign Minister Yitzhak Shamir was the only minister informed of this decision, which he endorsed. This marks the second time since the launching of the war whereby a decision of great importance was made without having been submitted to the government, and without prior deliberation.

The first time the government was faced with a fait accompli was when the Israeli Army entered East Beirut. Sharon later described the entry into West Beirut as "one of the most important decisions made during the Lebanon war."

At the Ministry of Defense in Tel Aviv, an ordnance survey map was hung at the office of General Sharon. The entire operation for the occupation of West Beirut had been previously drawn on the map. The name of the operation "IRON BRAIN," appeared in the upper margin. The top general staff finally received the long-awaited order.

Members of the government, like the rest of the Israeli public, did not learn that the decision to enter West Beirut had been made or carried out until the following day, when it was announced on the waves of Kol Yisrael (The Voice of Israel).

In an interview with the daily Ma'ariv, published two days after the entry into West Beirut, General Raphael Eitan (Raffoul) declared unhesitatingly:

"Now we are inside. We are going to mop-up West Beirut, gather all the weapons, arrest the terrorists, exactly like we did in Sidon and Tyre and in all other places in Lebanon. We will find all the terrorists and their leaders. "We will destroy whatever requires destruction. We will arrest those who need arrest. We will leave Beirut when an accord is reached and when our objectives in all of Lebanon are realized. When we withdraw from all Lebanese territory where our army is stationed today, then we will also withdraw from Beirut. But as long as all foreign forces have not been expelled from Lebanon, we shall not budge one inch, including Beirut."

Then, late at night on September 14, Israeli forces carried out their last preparations. At 11:00 P.M., Chief of Staff Eitan arrived at Israeli headquarters in Kafr-Sil, south of Beirut, and inspected the plan to occupy West Beirut with high-ranking officers...

* * *

II

Wednesday, September 15, 1982

ISRAEL OCCUPIES AN ARAB CAPITAL

Major General Amir Drori is a particularly important man within the Israeli General Staff. Commander of Israel's northern region, he was also responsible for the Golan Heights and the Lebanese territories occupied at the beginning of the war. This Wednesday, at 12:30 A.M., he received a new mission: to seize all key areas in West Beirut. The Israeli airlift intensified. One after the other, Israeli Hercules transport planes landed at the Israeli-occupied Beirut International Airport. Tons of arms and equipment were unloaded, and arriving paratrooper units were immediately transported by bus to advanced positions around West Beirut. Units of regular troops were used because there was no time to mobilize the reservists. Later, Chief of Staff Rafael Eitan declared: "Never in the history of Tzahal (Israeli Defense Forces) has an operation of such magnitude been executed with such speed."

At 3:30 A.M., even before the Israeli entry into West Beirut, a vital meeting took place at the headquarters of the Lebanese Forces -the unified militias of the Christian right, founded and previously headed by Bashir Gemayel. The meeting was attended by Israeli Generals Eitan and Drori. The Christian militias were represented by their top military commanders, headed by Fadi Frem, their commander in chief, and Elie Hobeika, chief of intelligence. Together they worked out the details of the Christian militiamen' s role in the takeover of West Beirut. On September 22, Ariel Sharon revealed to the Israeli Knesset that "the principle of Phalangist entry into the refugee camps of Beirut was discussed." At the end of the meeting, a Phalangist military commander admitted to the Israelis: "We have been waiting for this moment, for many years."

In his address to the Knesset on September 22, 1982, General Sharon declared that, the Israeli Northern Command constantly received the following instructions: "It was absolutely forbidden to go into the refugee camps. Search-and-destroy missions will be carried out by the Phalangists or the Lebanese Army." General Drori testified before the Commission of Inquiry that he had maintained "constant contacts" with the Phalangists throughout their stay in the camps.

Indeed, throughout the day, preparations for the Phalangist entry into the camps accelerated. They painted reconnaissance signs on the sides of buildings, featuring the letters MP (Military Police) and a triangle inscribed inside a circle, which is the insignia of the Lebanese Forces. They also drew arrows to indicate the direction of their operation from Shweifat in southeastern Beirut to the Kuwaiti Embassy just outside the refugee camps. Many residents of West Beirut testified later that the Lebanese Forces carried out these preparations during the early hours of the Israeli invasion, in order to mark precisely the road to be followed by their forces who were not familiar with the city.

The Israeli assault began at 5:00 A.M. The troops received orders to avoid civilian casualties, and not to fire except in case of armed resistance. The infantrymen moving behind armored vehicles advanced slowly from one building to the other, occasionally encountering awakening civilians. The primary objective was to seize the crossroads and the highest buildings overlooking the neighborhoods.

Israeli fighter-bombers began shortly after daybreak to make repeated low altitude passes above Beirut in a deafening display of force, yet without participating in the fighting. In the southern part of West Beirut, the homeless victims of previous fighting evacuated their temporary shelters in what used to be PLO headquarters in Fakehani to take refuge in neighborhood mosques for fear of eventual bombings by Israeli jets.

Swiftly, Israeli troops seized certain key positions, once occupied by soldiers of the Multinational Peacekeeping Force, who at the end of their mission, handed them over to the Lebanese Army. The latter immediately retreated before the Israeli advance, taking refuge behind secure buildings or in more distant places to observe the operations. The Israeli forces advanced on five axes encircling West Beirut, from the southern suburbs up to the port, north of the city. In the morning, the Israelis advanced along three prongs from the airport in the south:

1. Along the length of the coastal road from Ouzai toward the north as far as Corniche el-Mazra'a, which crosses the city from east to west,

2. Along the road running west of Sabra and Shatila toward the Sports Stadium,

3. Along the road running east of the camps, in the direction of the race-track (the hippodrome).

Later in the afternoon, they proceeded along two new axes:

4. From the port westward as far as the hotel district,

5. Over the Museum Crossing, from east to west.

Resistance to the Israeli advance was very weak: a few rounds of light artillery and anti-tank rockets (RPG). As pockets of resistance were identified, the Israelis would immediately direct their tank fire at them. Similarly, their naval fleet began to pound targets close to the seashore. Orders were given to avoid, at all costs, human casualties among Israeli troops. Ariel Sharon feared, above all, that large losses would tarnish his victory. Indeed, the casualty figures on the first day were very limited: 2 dead and 50 injured. Throughout the whole operation of occupying West Beirut, Israel sustained only 7 dead and approximately one hundred injured.

Likewise, according to the Lebanese press, the number of civilian casualties was put at 100 dead and 300 injured -certainly an insignificant number in comparison with the thousands of fatalities suffered since the beginning of the war.

Ariel Sharon arrived in Beirut at 9:00 A.M. to personally direct the Israeli campaign. He set up operations at Israeli headquarters located on the roof of a large building at the Kuwaiti Embassy crossroads, overlooking the city and the Sabra and Shatila camps. In the presence of Generals Eitan and Drori, he called Menachem Begin and declared: "Our troops are advancing toward their targets, I can see it with my own eyes."

During the day, fresh troops were dispatched toward Beirut. Several regiments of the ''Golani Brigade" were transferred by helicopter from Israel to Beirut International Airport. They were followed by tanks from the armored regiments of the same brigade, commanded by Colonel Eli Geva until his resignation.

The resistance offered by some leftist Lebanese militiamen, who decided to challenge the entry of the Israeli Army without waiting for directions from their parties, was surely symbolic in the face of the awesome Israeli war machine. Not only did these militias no longer have the recently withdrawn 15,000 Palestinian fighters and Syrian soldiers on their side, but the dismantling of military installations along the demarcation line three weeks earlier, and the mine-clearing of this area had opened a convenient path for the passage of Israeli armor.

To the north of the refugee camps few clashes occurred with the militias of progressive and Muslim forces, now united under the banner of the "Lebanese National Forces." However, with rare exceptions, the Israeli advance proceeded without surprises according to the projected plan. At 11:00 A.M., General Sharon even found time to go to Bikfaya to express his condolences to the Gemayel family. In response to a question asked during this occasion he stated: "History is not determined by one man or another." According to witnesses, he was accorded a cold reception. Earlier, a special envoy delivered a telegram. In the telegram Begin described the slain president-elect as a "great patriot who fought for the freedom and independence of Lebanon."

Israeli troops were issued express orders to disarm, in their advance, all Muslim and leftist militias. Thus, after the Palestinian departure, no other organized military force would remain in Lebanon alongside the weak official army, except the Lebanese Forces of the Christian right. From then on, the Phalangists faced a new situation, which they had not dared envisage, even in their wildest dreams. Colonel Zvi Elpeleg, Orientalist and former Israeli governor of Nabatiyyeh, explained: "ln Lebanese society, paradoxically, the continuous presence of armed civilians has been an element of equilibrium and mutual deterrence.

The entry of Israeli troops into West Beirut has subverted the existing facts. The Israelis have disarmed thousands of citizens, including members of the Shiite movement, Amal. Most of these were simple workers or peasants who bought these weapons with their meager savings for personal defense. These people, therefore, found themselves exposed, at the mercy of the Phalangists.'' (Ma'ariv, September 26, 1982).

Upon their entry into West Beirut, the Israelis immediately began searching for arms depots left in the area after the evacuation of Palestinian fighters. It is worth remembering that the Israelis prevented the guerrillas from transporting their heavy weapons with them, unlike the Syrian troop units who were permitted to leave town with all their equipment. During the withdrawal operations, a diplomatic incident actually occurred when departing Palestinians attempted to ship a few military vehicles. Eventually, these vehicles had to be unloaded in Cyprus to allow the Palestinians to proceed on their way.

According to the "Habib Agreements," the Palestinians had to transfer their weapons to the Lebanese Army as they withdrew. The latter, however, expressed little enthusiasm and was slow to enter West Beirut so that when Israeli troops took control of the city, they found numerous depots of heavy weapons, part of which were apparently handed to leftist militias by the PLO.

There were among the ranks of Israeli forces those who knew exactly where to find the arms depots. These were intelligence agents who had worked for years in West Beirut. The residents were stunned to see a peddler of cassette tapes (a vagrant named "Abu Rish" known to everyone as a harmless fool), a fireman and a door-keeper, good fatherly figures, leading Israeli units and pointing out caches of weapons and suspects for arrest.

The Israeli occupation of West Beirut provoked unanimous protest throughout the world. The Israelis were, above all, preoccupied with American reactions. At 9:00 A.M., on September 15, President Reagan's special envoy, Morris Draper, paid a visit to the prime minister in Jerusalem. He actually came to discuss the implementation of the second phase in the "Habib Agreement," namely, the withdrawal of all foreign forces from Lebanon. According to Ma'ariv, before allowing Mr. Draper to utter a word, Menachem Begin welcomed him saying:

Mr. Ambassador, I am honored to inform you that since 5 o'clock this morning, our forces advanced and took positions inside West Beirut. Our objective is to maintain order in the city. With the situation created by the assassination of Bashir Gemayel, pogroms could occur.

Begin did not mention the Israeli intention of allowing the Phalangists into the Palestinian camps. Very diplomatically, Morris Draper asked Begin if this involved a completely limited objective. After listening to the prime minister's explanations, Draper repeated: "I am happy to hear that the operation is restricted and very limited." Furthermore, throughout the day, Israeli spokesmen stressed that "the operation is limited as to its objectives and duration."

Menachem Begin's initial argument that the Israeli Army intervened to prevent pogroms and general chaos in West Beirut was repeated in all the Israeli statements. The next day it was included in the official government communiqué.

It was not until much later that Ariel Sharon gave a different explanation. In a television interview on September 24, he stated that the Israeli Army had been forced to invade West Beirut "because the terrorists left behind thousands of men, very large quantities of arms, headquarters and leaders." In a similar interview with Ma'ariv, Rafael Eitan alluded to "the thousands of armed terrorists hiding in Beirut and the refugee camps." Yet, a few hours before the assassination of Bashir Gemayel and the entry of Israeli troops into West Beirut, the same Rafael Eitan confirmed before the Knesset Committee on Foreign Affairs and Defense that: "Only a few terrorists and a small PLO office remain in Beirut." (Ha'aretz, September 15, 1982)

Indeed, throughout their two-week occupation of West Beirut (September 15-29), Israelis arrested and identified only a handful of fighters despite their systematic combing of the city. A spokesman for the Israeli Army refused to offer an exact figure. However, military sources confirmed that the number of those detained after the occupation of West Beirut did not exceed a few dozen. According to Assistant Secretary of State Nicholas Veliotes, Israel's claim that 2000 fighters remained in West Beirut after the evacuation of the PLO, was simply a pretext to seize that part of the city. Yet, the White House and the U.S. State Department refused to condemn the advance of Israeli troops, emphasizing the necessity of restoring quiet and stability.

Washington did in fact request the withdrawal of Israeli forces from Beirut, but within the context of a simultaneous withdrawal by Syrian and Palestinian forces stationed in Lebanon. The State Department conceded that the United States was not demanding immediate and unconditional pullback of Israeli troops from West Beirut, even though this constituted a violation of the "Habib Agreement."

Asked whether Washington sought an Israeli pullback, State Department spokesman John Hughes, declared: "Yes, but I am not giving you a scenario on how that will be done." Mr. Hughes added: "It would have been helpful if the Israelis had consulted Washington before making their move, but we accept the assurances given during the last few hours by the Israeli government."

Indeed, the State Department showed much understanding for the motive which had prompted Israel to enter West Beirut. An American diplomat in Washington told the French News Agency (AFP) that “the assassination of Bashir Gemayel created an extremely explosive situation in the city. The possibility that certain armed elements might take advantage of the situation had to be avoided at any price.”

Within a few hours, Israeli and international media began to reveal the enormity of the event. It was no longer a question of separating the feuding parties to prevent trouble and possible pogroms. It was a total takeover of the city. It was not until then that Secretary of State George Shultz summoned the Israeli Ambassador Moshe Arens in Washington. In a much less conciliatory tone he inquired about the true objectives of the Israeli government, and the anticipated deadline for the Israeli evacuation of Beirut.

In Israel, the Labor opposition appeared far more disturbed than the Americans over the operation waged by General Sharon. This was also the case of certain cabinet ministers who learned of the Israeli invasion of West Beirut on radio, and reacted vigorously. One minister, who preferred to remain anonymous, denounced, before the diplomatic editor of Ha'aretz, this "unprecedented scandal." (Ha'aretz, September 16, 1982), According to another minister, the defense minister seized this opportunity to accomplish what he had wanted for a long time, without obtaining approval from the government. Other ministers pointed out that Menachem Begin had undertaken to let the government ratify every decision pertaining to entering West Beirut, pointing out his failure to do so.

Davar, the daily of Israel's Labor Party, stated in its editorial that "Tzahal's (Israeli Army) place is outside Beirut." Labor Party leader Shimon Peres denounced this as "an adventurous operation." He demanded the withdrawal of Israeli troops from West Beirut and their replacement by a new international force. The proposals of the Labor leader were dismissed by Begin's advisers as "Nonsense."

PLO leaders were petrified by the news of the Israeli occupation of West Beirut. They had however, secured duly signed assurances from American envoy Philip Habib guaranteeing the safety of Palestinian civilians after the departure of all fighters from Beirut. Immediately, Farouq Qaddoumi, head of the PLO political department, declared: "We have been given a word of honor that Israel would not enter West Beirut, this promise was broken." Former Lebanese Prime Minister Sa'eb Salam, who for weeks had played the role of intermediary to conclude the "Habib Agreements" and to allow for an honorable departure of Palestinian fighters from Beirut, declared that the Israeli entry into the western part of the city was a violation of the signed accords. Senior State Department officials confirmed the view expressed by Sa'eb Salam. "Israel betrayed our trust," asserted Shafiq el-Wazzan, the prime minister of Lebanon.

In the field, the Israeli Army tried unsuccessfully to pressure the Lebanese Army to participate in the operations. Lebanese military leaders refused to collaborate, particularly in the Israeli suggestion to enter the refugee camps of south Beirut. In the evening, Major General Drori met with the Lebanese operations chief in the area, Colonel Michel Awn. The latter informed him that Prime Minister Shafiq el-Wazzan had ordered him not to collaborate in any way with the Israeli Army. The Lebanese officer was under orders to open fire on Israeli troops entering West Beirut. He stated that if he refused to do so he would be subject to trial by court-martial.

Colonel Awn proceeded to explain that since the Lebanese Army was "just then reconstituting itself as an organization. . .and just beginning to win the confidence of Moslem militiamen, Moslem residents and Palestinians of West Beirut," it could not allow itself to be compromised by collaborating with Israeli troops invading West Beirut. (New York Times, September 26, 1982). The Lebanese Army had its own agenda for taking control of the city and the Palestinian camps, according to Colonel Awn. A week earlier, for example, it had taken control of Burj el-Barajneh without any clashes or disturbances. According to this schedule, the takeover of the camps of Sabra and Shatila, situated to the north, would not be carried out until later.

The Israeli Army decided otherwise. As early as noon on Wednesday, the camps of Sabra and Shatila, which were not separated by any exact boundary, were surrounded by Israeli tanks pointing their guns at the camps. A little later, Israeli soldiers set up check-points around the camps, allowing them to control all entrances and exits. Anxiety began to mount inside the camps. The great majority of the inhabitants locked themselves inside their homes.

The PLO fighters -who had always defended the camps and resisted the siege of Beirut for weeks- were no longer there. No visible sign of their presence remained except for old posters glued to the walls of shattered homes.

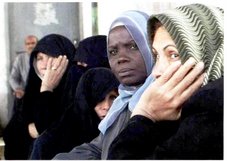

The Palestinian refugees of both camps -mostly elderly, women, and children- had avoided any confrontation with the Israeli Army for fear of reprisals. In anticipation of the rainy season, they had just begun to rebuild their homes shelled during the Israeli siege. Since the departure of the Palestinian fighters, all traces of armed presence in the camps had disappeared.

During the late afternoon and early evening, a few shells were fired by the Israeli Army in the direction of Sabra and Shatila. Norwegian Doctor Per Maehlumshagen, an orthopedic surgeon at Gaza Hospital situated to the west of Sabra, testified that the first wounded, about fifteen persons, started to be brought in that Wednesday evening. Others, generally victims of sniper fire, arrived the same evening at Akka Hospital, across the road that marks the southern edge of Shatila.

Zaki, an electrician from Sabra, recounted that he had accompanied other camp residents to an Israeli military post to express their fear of being captured by armed Lebanese groups. The Israeli soldiers reassured them, claiming that nothing would happen to them, "because they were civilians, not terrorists." Then, they ordered them to return to their homes.

A little after nightfall, electric power was abruptly cut off in all of West Beirut. The city was left in total darkness. A young Israeli soldier described how, at 10:00 P.M., his unit received an order to fire illumination flares above Sabra and Shatila starting at midnight. At the appointed time, the silence was broken with sporadic firing inside the camps. For the camp residents, this marked the end of another day, the 104th day of the Israeli-Palestinian war.

* * *

III

Thursday, September 16, 1982

“OUR FRIENDS ARE MARCHING ON THE CAMPS.”

“CONGRATULATIONS!”

The Israeli Army accomplished its mission by occupying all of West Beirut in thirty hours. At dawn on Thursday, the business district of Hamra was captured. Israeli tanks left great havoc in their path. They gutted residential buildings, destroyed shops and crushed vehicles. Hamra, which had recently recovered some of its pre-war appearance, suffered anew. Many businesses, just renovated after the August bombings, were once again damaged. At each intersection, the same tactic was repeated: tanks would point their guns at the axis of a large thoroughfare, then fire to open the way for the infantry. The soldiers would then advance in force, avoiding any entry into small alleys.

The residents spent the entire morning in shelters to protect themselves from Israeli guns, as well as from the rocket-launchers of the Lebanese left. Two columns of Israeli armor and infantry, one coming from the airport and the second from the port, joined together before noon near the American Embassy on Paris Avenue, one of the most beautiful thoroughfares in the Lebanese capital.

Around noon, West Beirut was entirely under Israeli control. For the first time in its history, Israel had conquered an Arab capital. At the offices of the Defense Minister in Tel Aviv, the Jewish New Year was being celebrated. Ariel Sharon took advantage of the opportunity to propose a toast and announce to his subordinates the success of his operation. The military spokesman declared in a communiqué: "Tzahal (Israeli Army) is in control of all key points in Beirut. Refugee camps harboring terrorist concentrations, remain encircled and closed.'' A military field report transmitted to headquarters in Tel Aviv indicated that only a few pockets of resistance were still holding and had not yet been cleared. The areas in question were Fakehani, where the PLO had its headquarters, and the camps of Sabra and Shatila.

The residents of both camps were awakened at dawn by the deafening noise of jets flying at low altitude. The camps were totally surrounded by Israeli troops. Snipers positioned around the camps began selecting their targets in the alleys. The first shells began falling from the surrounding hills and elevated ground. All day, the wounded poured into Gaza Hospital where doctors and nurses worked continuously. A number of patients were sent to al-Maqasid Hospital, 500 meters away.

Early in the morning, Christian militias began their preparations to seize the camps. After a conversation with Ariel Sharon, Rafael Eitan asked Major General Drori to verify for himself whether the Phalangists were well prepared to invade. At 8:00 A.M., an important meeting took place at Israeli headquarters. General Eitan detailed the tasks assigned to the Phalangists in the camps. The meeting was attended by General Saguy, director of military intelligence, a high-ranking representative of the Mossad and head of the General Security Services (The Shin Bet). About noon, Drori met with Fadi Frem, Chief of Staff of the Lebanese Forces.

He asked Frem whether his men were ready to enter Sabra and Shatila. The Phalangist officer responded: "Yes, immediately." Therefore, he was given the green light. The Phalangist troops left their bases to regroup near the International Airport. The force of about 1500 men followed the arrows and signs painted the night before on the walls of the city.

At 3:00 P.M., the commander of the Israeli forces in Beirut, Brigadier General Amos Yaron, and two of his staff officers met with Elie Hobeika, director of intelligence in the Lebanese Forces, and Fadi Frem, their chief of staff. With the assistance of aerial Photographs furnished by Israel, they coordinated the details of the Phalangist entry into the camps.

The Israeli general confirmed that his troops would supply all the necessary assistance: "to mop up the terrorists in the camps." Then, Major General Drori called Ariel Sharon to announce: "Our friends are marching on the camps. We have coordinated their entry." "Congratulations!" replied Ariel Sharon, "The operation of our friends is approved."

It is not known whether Drori informed the defense minister of what the Phalangist commanders had told him, namely that ''bones are going to be broken in the camps." After the massacre, Sharon stated before the Knesset that military leaders had specifically stated to the Phalangists that their forces "would enter the Shatila camp from the south and the west in order to comb it and purge it of terrorists. The civilian population, especially women, children, and the elderly, should not be harmed."

Several high-ranking Israeli officers, whose names are known today to some journalists in Israel, had strong reservations about the decision to authorize the Phalangist entry into the camps. They indicated that the Palestinian refugees who remained in the camps after the departure of the PLO forces, would be defenseless and risk being the object of bloody reprisals by Christian militias. On October 31, Major General Drori revealed before the Commission of Inquiry that one of his officers, named Reuven, had warned him against a possible Phalangist massacre of Palestinians.

It should be remembered that, before the beginning of the war on June 4, 1982, [1] after Phalangist participation in the fighting in West Beirut had been decided, high-ranking Israeli officers disapproved of the decision. They questioned Phalangist efficiency and discipline, insisting that the Israeli Army risked being compromised and smeared if Bashir Gemayel's men were to participate in the operations of West Beirut. Since the beginning of the war, these fears were heightened.

The men in the Lebanese Forces proved to be mediocre fighters with little motivation. The only battle in which they fully participated was the take-over of the Faculty of Sciences at Hadath. Even this battle could not have been won without the support of the Israeli Army. They have, however, shown much more determination against their Lebanese adversaries after the ruthless Israeli thrust into Lebanon. They were particularly aggressive against the Druze, killing dozens of civilians in the villages of the Shouf and the Aley district. For example, when the Israeli Army, with government orders, allowed the Phalangists to enter the Druze village of Souq el-Gharb, killed fourteen villagers during a wedding ceremony.

Elsewhere, the Phalangists requested permission from the Israelis to attack a hill on the Beirut-Damascus highway, where Palestinian troops were entrenched. On their way, the Phalangists changed their objective, deciding instead to attack the Druze, their sworn enemies. After a deadly battle, the Israeli Army had to intervene to prevent a Phalangist defeat. The Israelis lost one soldier in this particular battle. Furthermore, complaints of violence, theft, rape, and confiscation of property, committed by Phalangists in the territories occupied by the Israeli Army, have been brought before the Israeli command since the early days of the war. Some of these cases were reported by the Israeli press.

Eitan Haber, the military correspondent of Yedi'ot Aharonot, the most widely read Israeli daily, described the Phalangists in these words: "The high authorities in the army have known for a long time that the Phalangist fighters (if we can call them 'fighters'), are nothing but a gang of youths, and the not-so-young, whose level of combat is rather poor and whose morality is even more dubious. Some of them who established roadblocks in Beirut were bribed by the terrorists [PLO fighters] and accepted hard cash to close their eyes and allow the passage of food and other banned goods during the blockade of West Beirut. They are moreover, an organized mob, with uniforms, motorized units, and training camps, who have become guilty of abominable and cruel deeds."

This opinion is shared by a majority of Israeli military correspondents who came to know the Phalangists well, particularly those who received military training in Israel. Since 1976, which marked the beginning of their collaboration with the Israelis, Phalangist militiamen have received military training in Israeli Army camps within Israel proper.

The Phalangists never concealed from the Israelis their intention to massacre the Palestinians. Testimonies to this effect are numerous, and have been reported in the Israeli press. The most impressive testimony was cited by Knesset Deputy Amnon Rubenstein, a member of the small centrist political party, Shinui.

In the Knesset debates which followed the announcement of the massacre in Sabra and Shatila, Mr. Rubenstein recalled that during a visit by Israeli parliamentarians to Israeli-occupied south Lebanon, he met members of the Phalangist Party who resolutely expressed their intention to massacre the Palestinians. One of them said: "The death of one Palestinian is pollution; the death of all the Palestinians is the solution."

Bamahaneh, the official weekly voice of the Israeli Army, wrote on September 1, 1982 (two weeks prior to the massacre) that "A high-ranking Israeli officer heard the following words uttered by a Phalangist officer: 'The question we ask ourselves is: what should we start with? Rape or murder? ... If the Palestinians have any common sense, they should try to leave Beirut. You do not have any idea of the slaughter to befall the Palestinians, civilians or terrorists, who will remain in town. Their attempt to blend into the local population will be futile. The sword and gun of Christian fighters would pursue them everywhere and will exterminate them once and for all.' "

On many occasions, Israeli officers in constant contact with the Christian forces heard such remarks as: "We'll cut their throats," or "blood will be knee-deep." After learning of Sharon's decision to authorize Phalangist entry into the camps, an Israeli officer reacted by stating: "He who allows a fox into a hen-house should not be astonished if the chickens are devoured."

Another Israeli officer, who served a long time at the headquarters of the northern front, said: ''The Lebanese Forces resemble the militias of Sa'ad Haddad. They both pose as heroes in the face of unarmed civilians." He recalled that during the ''Litani Operation'' of March 1978 (the first Israeli invasion of south Lebanon), Haddad's troops were content to follow the Israeli Army, ransacking and killing along their path. All the inhabitants of the village of Khiyam were savagely massacred and all their possessions loaded on trucks by Haddad's men.

Nothing better illustrates the state of mind prevalent at the Israeli command than the following minor event reported by the Labor daily, Davar. After Ariel Sharon had decided to authorize the Phalangists to "mop-up the camps," an officer suggested that an Israeli liaison officer should accompany them on their mission. However, a higher-ranking officer rejected the idea on the spot. He argued that one would expect the Phalangists to commit irregularities, thus, it would be unwise for the Israeli Army to be involved. This same officer knew that the operation was led by Elie Hobeika, an old acquaintance of the Israelis, and was also aware of the implications of Hobeika's involvement.

The first Israeli contacts with Hobeika date back to 1976 when, at the request of Israel, he was sent by Bashir Gemayel to south Lebanon. The purpose of this mission was to support, with several dozen men, the activities of Sa'ad Haddad in his enclaves along the Lebanese-Israeli border. Hobeika, who was only 22 years old, according to the Israeli press, had already proved himself by murdering several Lebanese and Palestinian civilians. Subsequently, the Israelis decided to get rid of him, sending him back to avoid being tainted by his "irregular" activities. However, all contacts with him were not severed. According to the American press, he served as liaison with the CIA and the Mossad (Israeli Intelligence agency) in his capacity as head of intelligence in the Military Council of the Lebanese Forces. Hobeika also received some training in Israel.

This time, it was with Israel's blessing that Hobeika and his men entered the Palestinian camps. According to an Israeli television reporter, Hobeika summoned his principal collaborators to his headquarters. The group included his assistants, Emile Eid and Michel Zuwein; the commander of the Phalangist Military Police, Deeb Anastaz; the commanding officer of East Beirut, Maroun Mich'alani; the chief of commandos, Joseph Edde; and the permanent liaison officer with the Israeli forces, Jessy -who had been telling everyone for months that there was no other solution but to massacre the Palestinian residents of the camps in Beirut.

A Phalangist unit of 150 men, assembled near the airport, began to move. It advanced northward through Ouzai, along the Henri Chehab army barracks, reaching the headquarters of the Lebanese Forces which were established in a United Nations building at the Kuwaiti Embassy traffic circle. At the same intersection, but across the street to the north, the Israelis set up a command and observation post in an apartment building which housed the Lebanese Army officers. It is located 200 meters from one of the massacre sites in Shatila. From the roof of this seven-story building, "it is possible to see into at least part of the Shatila camp, including those parts where piles of dead bodies were found later." (New York Times, September 26, 1982).

The Israeli soldiers who manned roadblocks at the entrance of the Shatila camp received an order by radio to allow the Phalangist forces into the camp at sunset. Testimony by the residents of Bir Hassan, a camp located near the Henri Chehab army barracks, revealed that the first contingents of Christian militias (25 jeeps) passed through their area at 4:00 P.M., headed toward the Kuwaiti Embassy. Frightened camp residents went to Israeli headquarters where they were told to return home and not to worry. The civilians did not follow the advice of Israeli officers. Instead they slept in a building near the beach and sought refuge the following day at the Henri Chehab barracks. According to the testimony of the survivors in Shatila, several units entered the camp before 6:00 P.M. They testified that the first massacre took place before nightfall in the Arsal neighborhood across from Israeli headquarters.

Several testimonies agreed as to the identity of the murderers. Most of them were members of the Lebanese Forces, that is, essentially Phalangist militias of the Kata'ib Party, founded in 1936 by Pierre Gemayel upon his return from Germany. In addition to the Phalangists, the Lebanese Forces included "The Tigers," the militiamen of the National Liberal Party headed by ex-President Camille Chamoun; and another group of rightist militant extremists known as "The Guardians of the Cedar," led by Etienne Saqr.

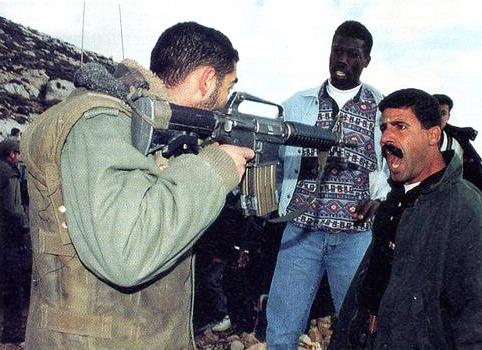

The armed gangs streaked across the camp aboard the jeeps furnished by the Israeli Army. They wore dark green uniforms embellished with their insignia, familiar to all Lebanese. Some were armed with knives and hatchets. These units belonged to the Phalangist Intelligence, Military Police and Commandos.

Afterward, camp residents affirmed fervently that Sa'ad Haddad's men had also taken part in the carnage. They identified them by their badges, and especially by their distinct southern accents and names. While the 12,000 men of the Lebanese Forces are exclusively Christian, Sa'ad Haddad's troops (approximately 6000 men) included a large number of Shiites. Refugees in Shatila heard uniformed soldiers calling each other by such first names as Ali and Abbas, which are typical Shiite names.

Sa'ad Haddad himself has formally denied any participation by his troops in the massacre. However, in a discussion with Israeli journalists, he added: "Some members of my army have joined the forces of Bashir Gemayel. It is possible that these deserters, wearing the insignia of ‘Free Lebanon' might have taken part in the massacre.'' An Israeli commander confirmed that some members of Haddad's militia were apprehended by the Israeli Army after the carnage. Haddad argued that the men in question numbered three or four "who tried to rescue their families living in the camps after the carnage was announced." In any case, according to Haddad, "Every move we make has to be coordinated with the Israeli Defense Forces. We have strict orders not to cross north of the Awali River." (The Times, September 23, 1982).

In spite of Haddad's denials, residents of Shweifat and Khalde, two small villages located south of Beirut, confirmed to journalists that military convoys of Haddad' s ''Free Lebanon'' forces were seen heading toward the airport from the south. While the massacre was unfolding, an Israeli television correspondent reported meeting a mechanic from Saad Haddad's forces at the airport. The militiaman received his training in Israel and spoke Hebrew. A reliable source also established that a member of Saad Haddad's troops was killed by the Israelis Friday night, while prowling about the Sports Stadium. Furthermore, the words "Sa'ad Haddad" and "Kata'ib" were found painted on the walls in several locations throughout Sabra and Shatila. It is also well known that members of Haddad's "Free Lebanon" militia were seen conversing with Israeli soldiers in West Beirut the day following the massacre. However there is no doubt that their participation in the massacre was limited. Although more than 400 men entered the camps at the height of the carnage, the number of Haddad's men never exceeded a few dozen. As for Sa'ad Haddad himself, he did not arrive at Beirut until Friday morning at 9:00 o'clock. He flew aboard an Israeli helicopter on his way to Bikfaya to express his condolences to the Gemayel family. According to this account, he left the capital on Friday afternoon.

Various accounts are in full agreement concerning the precise time of the assailants' entry into the camps. According to Israeli soldiers present in the area, the time of entry was 5:15 P.M. Camp residents confirm that the first organized murders began at 5:00, or even a little earlier in certain locations in Shatila. Ariel Sharon declared before the Knesset that "the forces entered [the camps] at night." Furthermore, everyone agrees that the attackers entered from two directions: from the south through the main road leading to the camps, and from the southwest coming down the hill near the Kuwaiti Embassy. Leading the campaign was Elie Hobeika.

The carnage began immediately. It lasted forty hours without interruption. The Israelis were able to observe the operations from the roof (seventh floor) of the three Lebanese buildings they had occupied since September 3. They were equipped with telescopes and binoculars with night-vision. In reality, they did not need this equipment because they were only 200 meters away from the major location of the carnage. During these two days, the building swarmed with officers. There was an endless flow of traffic in and out; vehicles of the signal corps, armored vehicles and different units all around.

To quote one Israeli officer, watching from the roof of these buildings was like watching "from the front row of a theater." Furthermore, Israeli forward positions manned by paratrooper units were very close to the edges of the camps, and Israeli "Merkava" tanks commanded a view of the area. In addition, Battalion 501 of the Lebanese Army was stationed at the Kuwaiti Embassy traffic circle.

According to the survivors, the massacre immediately assumed grave proportions. During the first hours, Phalangist militiamen murdered hundreds of people. They shot everything that moved in the alleys. Tearing down doors, they barged inside and liquidated whole families at the dinner table. Residents were murdered in bed, still wearing their pajamas. In many apartments, children, three or four years old, were found in their pajamas and blood-soaked blankets. Quite often, the murderers were not content with sowing death.

In too many cases, the assailants dismembered their victims before killing them. They smashed the heads of children and babies against the walls. Women, and even little girls, were raped before they were killed with hatchets. Often, men were dragged out of their houses to be summarily executed in the streets.

With their hatchets and knives, the militiamen spread terror as they indiscriminately slaughtered men, women, children, and the elderly. Quite often, they would spare the life of a single family member -killing the rest in front of his eyes, so he could later recount what he saw and lived through. At the same time, they did not distinguish between Christian and Muslim, Lebanese or Palestinian. All who lived in the refugee camps met the same fate. A young Shiite girl related how her parents fell to their knees before their butchers. They begged to have their lives spared, swearing that they were Lebanese. The murderers responded: "You have lived with these Palestinian scoundrels; your fate will be like theirs." Then they killed all the members of the family except the witness.

Among the victims of the massacre were nine Jewish women who had married Palestinian men during the British Mandate and accompanied their husbands to Lebanon during the 1948 exodus. The names of four of these women were published by the Jerusalem Post of September 30, 1982. In the Horsh Tabet area, the whole Miqdad Lebanese family, originally from Kisrawan, operated a garage in Shatila for more than thirty years. Its 45 members -men, women and children- were executed without exception.

Some had their throats cut, others were disemboweled, among them a 29 year old woman named Zeinab. The woman, in her eighth month of pregnancy, was disemboweled and her fetus placed in her arms. Her seven other children were also murdered. Another relative, Wafa Hammoud, 26 years old and in her seventh month of pregnancy, was also killed with her four children. In this same neighborhood, several other women were raped before being murdered. They were then disrobed and their bodies arranged in the form of a cross. One of the raped young girls was a 7-year-old daughter of the Miqdad family.

Milad Farouq, 11 years old, was wounded in the arm and the leg. After being taken to Gaza Hospital for treatment, he described how his mother and young brother were killed while watching television. The militiamen entered the house, and without warning shot everyone at point-blank. Then, they left without uttering a single word.

Some camp residents had enough presence of mind to escape as fast as possible upon hearing the first shots and the voices of screaming victims. One such person is Mrs. Hashem. Upon hearing the dreadful noises coming from the south, she left her shanty at Shatila and ran with her husband and children to seek refuge farther to the north. She still did not realize that a premeditated massacre was being carried out. Hence, after locating a shelter, she asked her husband to return home and bring a little food from the refrigerator, particularly milk for the children. She was never to see him alive again. On Saturday, his bullet-riddled body was found at their home.

The militiamen were not content to torture and kill. They also looted: hands of women were cut at the wrists to remove their jewelry. An Israeli journalist reported the following testimony by a resident of Shatila:

On Thursday night, the Phalangists entered my brother's apartment. They demanded that he give them all the money he possessed. He brought them 40,000 Lebanese pounds and two kilograms of gold. But this did not satisfy them. They asked him to sign a check for 500,000 pounds. My brother did what they asked. After he finished signing the check, they told him: "You see, now you are worthless." They they killed him, his father, and his two brothers. Only his wife and two daughters managed to escape from the apartment and survived.

A 13-year-old Palestinian girl was the sole survivor of her family. She lost both parents, her grandfather and all her brothers and sisters. She recounted the following in the presence of a Lebanese officer:

We stayed in a shelter until very late on Thursday night. Then I decided to step outside with my girlfriend. We couldn't breathe anymore. Suddenly, We saw the Phalangists arrive. We ran back to the shelter and warned the others. Some people came out of the shelter brandishing a white handkerchief. They walked toward the militiamen shouting: ‘We are for peace’. They were immediately gunned down. The women screamed and pleaded I ran and hid in the bathtub of our apartment. All the others were killed. Afterward, I saw them march people nearby and execute them. I tried to look out of the window, but a militiaman saw me and shot at me. I returned to the bathtub and remained there for five hours. When I came out, they captured me and threw me with the others. They asked me if I were Palestinian and I answered in the affirmative. They said: ‘Then, you would like to occupy Lebanon?’ ‘No, we are ready to leave here,’ I answered. Next to me, my nine-month old nephew cried constantly. This unnerved one of the soldiers who suddenly said: 'I have had enough of his crying,' shooting my nephew in the shoulder. I began to cry and told him that the baby was the only child left in my family. But this unnerved him more, so he grabbed the baby and tore him in half.